Joerg Stolz, sociologist at the University of Lausanne. © Felix Imhof

Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism... Major religions around the world are losing followers according to a remarkably similar pattern that plays out in three phases over roughly two centuries. These are the findings of an international study published in Nature Communications, conducted by researchers from the universities of Lausanne, Oxford, and Maryland, based on data from more than 100 countries. Here is an interview with the study's lead researcher, sociologist Jörg Stolz.

Your study claims that religious decline follows three distinct stages everywhere in the world. Can you explain this phenomenon?

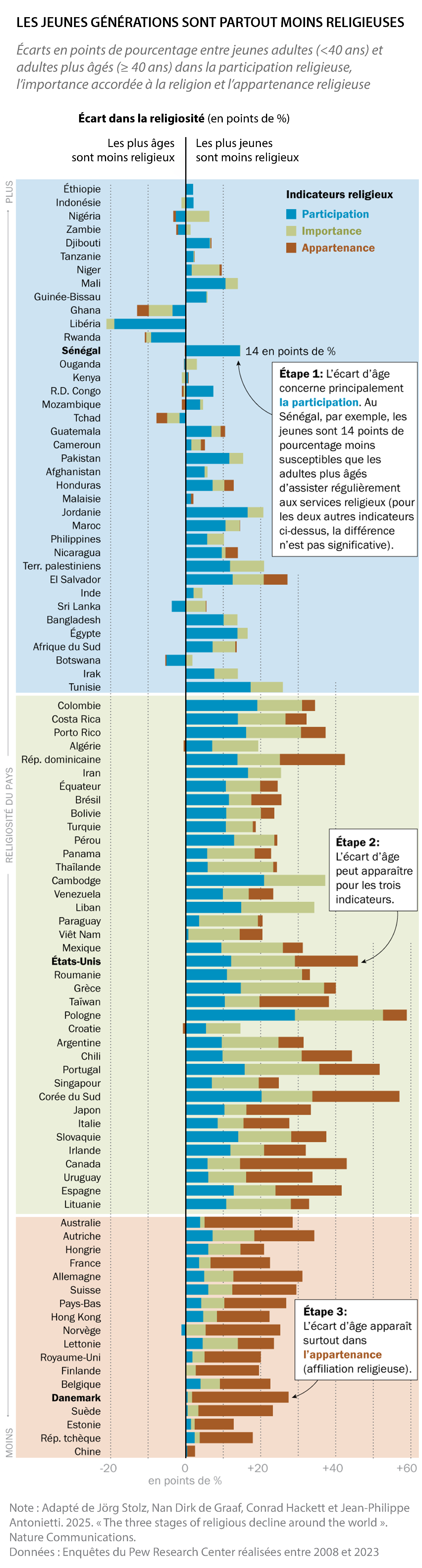

We analyzed data from over 100 countries and discovered a recurring pattern: religiosity always declines in the same order. First, people stop attending religious services — it's the most time- and energy-consuming aspect. Then, they stop considering religion to be important in their personal lives. Finally, they abandon their religious affiliation. We call this the Participation-Importance-Affiliation sequence.

You analyze over 100 countries. Do they all follow this pattern?

Almost all of them. What's remarkable is that this model works for majority-Christian countries, but also for majority-Buddhist, Hindu, and even Muslim countries. Some colleagues thought that secularization was solely a Western Christian phenomenon. Our data shows otherwise.

But there are still exceptions...

Yes, notably post-Soviet Eastern countries like Russia or Georgia. These countries are experiencing the opposite phenomenon: a religious revival. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, there were major economic, political, and identity crises. One of the only institutions that continued to function was the Orthodox Church. The state that came after legitimized itself through this orthodoxy. In Georgia, we observe the most spectacular revival of all.

So an economic crisis can reverse the trend?

Exactly. The secularization mechanism works when there is modernization: people earn enough money to live relatively well, they feel secure. During a major crisis such as that of the former Soviet Union, this mechanism no longer works. That's why these countries are the exception. Conversely, in most African countries, for example, the Human Development Index—which measures longevity, GDP, literacy—is constantly improving, even if the situation may seem unstable.

What's innovative about your methodology?

The central idea, which we owe to the British sociologist and secularization specialist David Voas, is to rank countries according to their religiosity and treat this as a theoretical time axis. This is a bold approach: we're saying that not all countries are experiencing these 200 years of transition simultaneously. Africa has only just begun, Europe is well advanced, the Americas are somewhere in the middle, and Asia has highly developed countries that are already far into the transition, like Hong Kong and South Korea.

Where does Switzerland stand in this process?

Switzerland is in the third stage. Most people no longer participate in religious rituals or find religion important in their lives. However, older people still mostly belong to historic churches, whereas younger people are abandoning this affiliation. Switzerland is absolutely not an exception, by the way. It’s following exactly the same path as other Western European countries. What's striking is the mechanical nature of the process: each generation born every ten years is systematically slightly less religious than the previous one. Swiss society is secularizing through generational replacement—new generations are arriving with a lower level of religiosity. It's a slow but relentless process, and this is precisely why we can predict it so reliably.

How long does this transition take?

About 200 years. Unless there's a major crisis—a third world war, the destruction of the welfare state. Then everything can change. But under stable conditions, the process is predictable.

Will religion eventually disappear completely?

One thing is certain: we'll have much less religion. But Europe already has much less religion today than before. It's incredible how important religion was 100 or 200 years ago. In Switzerland, our last war was a war between Protestants and Catholics. We found it so important! Today, we think it's absurd.

Some fear that with the decline of religion, moral values will also disappear...

We can ask the question, but empirically, we don't get the impression that countries with less religiosity are doing worse in terms of values and prosocial behaviors. Take Sweden, a very unreligious country: people behave well, there's hardly any theft, if someone forgets something, people will return it. Parents teach their children to say hello, thank you, not to be selfish. Whereas in very religious countries, there's often a lot of corruption, a lot of violence.

Is religion being replaced by other forms of spirituality?

That's a big question. Some claim that spirituality remains stable, simply replaced by a more individualistic spirituality: yoga, meditation, tarot, magic. But according to our data in Europe and the United States, that's not how it's happening. There's no real replacement. Holistic spirituality is just barely managing to remain stable, but it's not growing. It will never fill the void left by religion.

Why, in your view?

Because people need religion less. Religion fulfills needs, but only symbolically. It was a remedy for everything. In the case of illness, people would make a pilgrimage to be healed. Today, we have medicine. The big existential questions—such as why the world exists—were major religious themes, but today physics explains how things probably happened. For security, we have the welfare state, insurances. We can still pray, but we need it less. This is why the void doesn't need to be filled by something else.

Interview by Kalina Anguelova

Stolz J, de Graaf ND, Hackett C, Antonietti JP. The three stages of religious decline around the world. Nat Commun. 2025 Aug 19;16(1):7202. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-62452-z.